Blog

Jewellok is a professional pressure regulator and valve manufacturer and supplier.

New Hospital Projects: Key Considerations in the Design and Selection of Medical Gas Valve Systems

- Pressure Regulator Valve Manufacturer

- adjustable propane pressure regulator, adjustable propane regulator, air compressor non return valve, argon gas pressure regulator, argon hose connector, automatic switching valve, electric water valve, gas manifold system, gas pipeline valve, gas pipeline valves, gas regulator, gas semiconductor, high flow co2 regulator, high pressure argon regulator, high purity regulator, high purity regulators, high purity valves, humming propane regulator, industrial regulators, laboratory gas valves, low pressure gas regulator, low pressure regulator, medical gas changeover manufacturer, medical gas changeover market, medical gas changeover supplier, Medical gas changeover system, Medical Gas Valve Systems, Medical Gas Valve Systems Manufacturer, Medical Gas Valve Systems Supplier, oxygen regulator gauge, pressure regulator, pressure relief valve vs safety valve, pressure safety valve vs relief valve, propane adjustable pressure regulator, propane pressure regulator valve, safety or relief valves, safety valve and relief valve, safety valve and relief valve difference, safety valve vs pressure relief valve, second stage propaneregulator, single stage pressure regulator, stainless pressure regulator, two stage pressure regulator, valve timer water, what is a flame arrestor, what is a gas pressure regulator

- No Comments

New Hospital Projects: Key Considerations in the Design and Selection of Medical Gas Valve Systems

Medical gas valve systems are the silent lifelines of modern healthcare facilities. From the oxygen supplied to an ICU ventilator to the surgical air powering a pneumatic drill in an operating theatre, the reliability of these systems directly impacts patient outcomes. However, in many new hospital projects, piping and valve systems are treated as afterthoughts—commoditized components selected based solely on budget. This approach is flawed. This article provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the critical design principles and selection criteria for medical gas pipeline networks and valve assemblies in greenfield hospital construction. We will explore material science requirements, network architecture redundancy, valve typology, installation quality assurance, and the integration of alarm systems, providing a roadmap for engineers and project managers to deliver compliant, future-proof infrastructure.

1. Beyond the Pressure Test

The landscape of hospital construction is changing. With the rise of hybrid operating rooms, MRI-compatible anaesthesia units, and increasing domestic medical gas consumption, the static piping designs of the 1990s are no longer sufficient. The primary challenge in new projects is no longer simply achieving the required flow rate at the terminal unit; it is achieving resilience.

A significant percentage of commissioning delays in new hospitals stem from contaminated or incorrectly installed pipeline systems. These issues are expensive to rectify once walls are sealed. Therefore, the design and selection phase must prioritize three pillars: Purity, Pressure Integrity, and Pathway Redundancy.

2. Regulatory Framework and International Standards

Before specifying a single fitting, the project team must establish the governing standard. While local codes vary, the international benchmark remains ISO 7396-1 (Medical gas pipeline systems), with HTM 02-01 (UK) and NFPA 99 (US) providing region-specific nuances.

A common mistake in international projects is the mixing of standards—for example, using ISO-compliant purity requirements but NFPA-required shut-off valve spacing. The design basis must be singular and consistent. For greenfield projects, adopting the most stringent requirements for cross-sectional area and material thickness often proves cost-neutral in the long run, as it accommodates future capacity increases without a full re-pipe.

3. Pipeline Network Architecture: The “Ring Main” vs. “Dead-End” Debate

For new hospitals exceeding 10,000 square meters, the design of the distribution network is critical.

3.1 The Case for the Ring Main

While dead-end radial systems are simpler and cheaper to install, they present a single point of failure. If a section of pipe downstream of a zone valve is compromised in a radial system, that entire zone goes offline.

In a Ring Main configuration, medical gas is supplied to a zone from two directions. This allows for sectionalization—maintenance or repair can occur on one leg of the ring while supply is maintained via the alternate path. Although initial costs are roughly 15–20% higher due to increased pipe runs, the operational continuity offered during the 30-year lifecycle of a hospital justifies the investment, particularly for Oxygen and Medical Air.

3.2 Riser Design

In multi-story buildings, vertical risers should be sized not only for current peak demand but also for the conversion of adjacent floors. It is prudent to include one or two spare “future” risers capped with isolation valves in the main plant room.

4. Material Selection: Copper is Not a Commodity

The default material for medical gas valve systems is copper. However, not all copper is equal. A frequent specification error is the substitution of standard plumbing grade (ASTM B88 Type L) for medical gas specific tubing.

4.1 Specification Requirements

For medical gas applications, copper must be:

-

Type K or L: with Type K preferred for buried or embedded installations due to thicker walls.

-

Cleaned and Capped: The tubing must be manufactured to a standard that ensures it is free from oil, grease, and debris. It must arrive on site with end caps intact.

-

Brazing vs. Soldering: This is non-negotiable. Joints must be brazed using a filler metal containing a minimum of 45% silver (BCuP-5). Soft solder (tin/lead) has a lower melting point and is prohibited due to risk of joint failure in fire conditions.

4.2 Alternative Materials

While rare, 316L Stainless Steel is sometimes specified for Vacuum systems in highly corrosive environments or for high-pressure Nitrous Oxide networks. However, for standard medical air and oxygen, cleaned copper remains the gold standard for its bacteriostatic properties and ease of installation.

5. Valve System Design and Selection

Valves are the control nodes of the hospital. If the pipe is the artery, the valve is the heart valve. Poor valve selection leads to pressure drops, inability to isolate, and cross-contamination risks.

5.1 Main Line Valves (Plant Room)

At the source (manifold or generator), full bore ball valves are standard. However, the key feature often overlooked is the “Tell-Tale” drain valve. A small bleed valve installed upstream of the main shut-off allows maintenance staff to verify the line is fully depressurized before attempting service.

5.2 Area Zone Valve Service Units (AVSUs)

Every clinical zone (ward, ICU, theatre suite) must be isolatable via an AVSU.

-

Typology: The industry standard is a “Ball valve” with a lever handle. However, for high-usage areas, consideration should be given to low-torque ball valves to ensure that staff with reduced hand strength can operate them during emergencies.

-

Configuration: The AVSU must be contained within a lockable box with a sight glass. A common design flaw is placing the AVSU inside the ceiling void above the clean corridor. It must be accessible at a “standing height” location.

-

Three-Piece Design: Specify three-piece body ball valves for AVSUs. Unlike one-piece valves, three-piece valves allow the center section to be removed for repair or replacement without unsweating the pipe ends, a critical feature for maintaining hygiene in an operating environment.

5.3 Pressure Regulating Stations

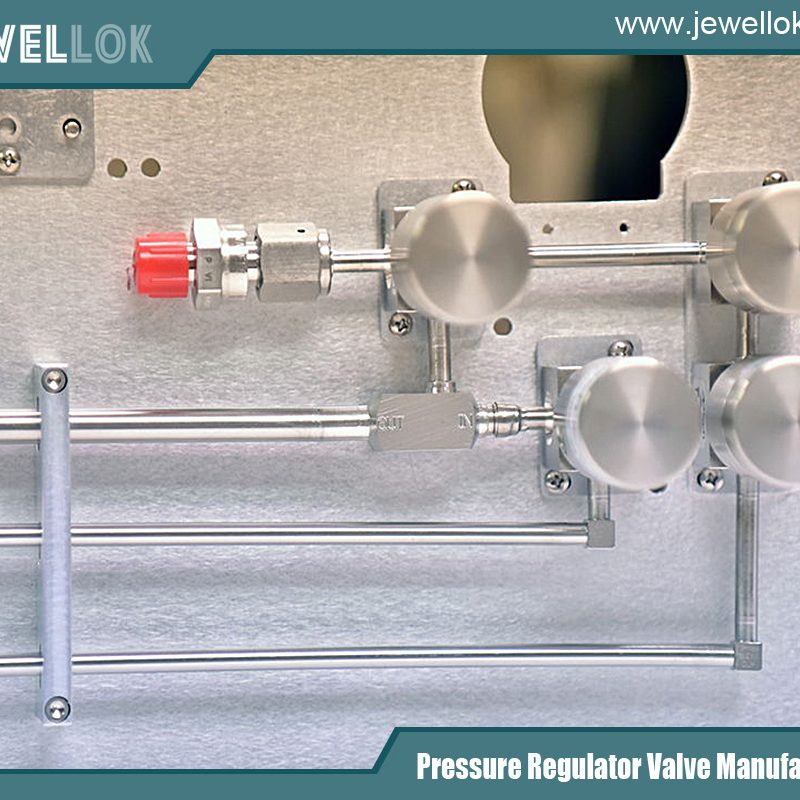

Most equipment operates at 4 bar (Oxygen/Air) or 7 bar (Nitrogen). Line pressure regulators must be of the “dead-end” capable type, designed to remain tight against a sealed outlet without creeping (increasing downstream pressure). Creep is a common failure mode; selecting regulators with elastomeric diaphragms (e.g., EPDM) specific to medical gases is essential.

6. Sizing and Flow Dynamics

Under-sizing pipelines to save capital expenditure is a false economy. Engineers must perform dynamic flow calculations, not just static pressure loss calculations.

6.1 Diversity Factors

ISO 7396 allows for diversity factors—assuming not every outlet will be used simultaneously. However, in modern ICUs, bed occupancy is nearly constant, and portable dialysis machines often require connection to medical air. A conservative approach is recommended: reduce diversity factors by 10-15% compared to standard tables to buffer against future equipment density.

6.2 Velocity Limits

To prevent noise generation and erosion-corrosion at bends, velocity limits must be respected:

-

Copper Pipelines: ≤ 10 m/s for Oxygen and Medical Air; ≤ 15 m/s for Vacuum.

-

Pressure Drop: Maximum allowable pressure drop from source to outlet is typically 5-10%. If calculations exceed this, the pipe diameter must be increased.

7. Installation and Verification: Ensuring Integrity

A perfect design is worthless if installation is sloppy. For new projects, the specification must mandate a “Clean Build” policy.

7.1 Contamination Control

Piping must remain capped 24/7. If a pipe is left open overnight, moisture and construction dust ingress occurs. This dust combines with oxygen flow to create a combustion hazard (particle impact ignition). The project specification should require “bungs” or plastic caps on every open end at the end of each workday.

7.2 Brazing Atmosphere

Oxygen pipelines are particularly sensitive. When brazing, oxygen reacts with carbon residues to form combustible deposits. Therefore, brazing must be carried out with an inert gas purge (Nitrogen or Argon) flowing through the pipe. This prevents oxidation inside the pipe (firescale), which can flake off and block valves or damage equipment.

7.3 Testing Regimes

The test sequence is critical:

-

Strength Test: Usually 1.5x operating pressure.

-

Tightness Test: Holding pressure for 24 hours to detect microscopic leaks.

-

Cleanliness Test: Wiping the internal bore with white gauze to check for particulate and oil residue.

8. Integration with BMS and Alarm Systems

Valves are now “smart.” While manual isolation remains the fallback, new projects benefit from integrating critical valve position sensors into the Building Management System (BMS).

8.1 Position Indication

Specify valves with factory-fitted proximity sensors to indicate “Valve Open” or “Valve Closed” status at the central monitoring station. In a code blue scenario, the facilities manager should not have to run to the valve box to confirm isolation; this data should be visible remotely.

8.2 Pressure Monitoring

Digital pressure transducers should be installed immediately downstream of each AVSU. This allows the BMS to generate trend data. A gradual pressure drop over time indicates a developing leak; early detection can prevent a catastrophic failure.

9. Common Pitfalls in New Construction

Drawing from recent project post-mortems, three specific pitfalls should be highlighted:

-

The “Capped Sleeve” Error: Engineers often specify capped sleeves through firewalls, but the annular space between the sleeve and the gas pipe is not properly fire-stopped with an intumescent sealant. This violates fire compartmentation.

-

Condensate in Vacuum Lines: Vacuum systems carry liquid effluent. Horizontal runs must be pitched (sloped) back to the plant room or to low-point drains. Failure to do so results in “gurgling” sounds at the patient terminal and potential blockages.

-

Valve Accessibility: Architectural layouts frequently place AVSUs behind door swings or in corners where a valve handle cannot achieve full 90-degree rotation. This must be reviewed during the 3D BIM coordination phase.

10. Conclusion

The design and selection of medical gas valve systems in a new hospital is a discipline requiring respect for chemistry, physics, and human factors. It is not a low-voltage electrical system; it is a high-precision mechanical fluid system where the fluid is life support.

To achieve excellence, the project team must move beyond the mindset of “pipe and fittings.” They must view the network as a holistic safety device. By specifying high-purity copper, implementing robust brazing practices with nitrogen purge, selecting maintainable three-piece valves, and designing for redundancy via ring mains, a new hospital can ensure that its gas systems remain invisible, reliable, and safe for decades.

The upfront cost differential between a compliant system and a merely “functional” system is marginal. The cost of failure—in terms of patient safety, surgery cancellations, and remedial construction—is catastrophic. Prioritize the pipeline, and the hospital will breathe easy.

For more about new hospital projects: key considerations in the design and selection of medical gas valve systems, you can pay a visit to Jewellok at https://www.jewellok.com/ for more info.

Recent Posts

How to Choose the Krypton Gas Ultra High Purity (UHP) Regulator

Troubleshooting Common Failures in TMA Gas Changeover Manifolds

Key Specifications: UHP Argon Valves for 99.999% Purity Gas Systems

Tags

Recommended Products

-

Ultra High Purity Trimethylaluminum TMA Gas Cabinet Liquid Delivering Cabinet Used For Specialty Gas Delivery System In Semiconductor

-

Stainless Steel Ultra Clean Welding Joint Fittings TW Series TRW Series & CW Series

-

Ultra High Purity Gas Delivery Systems And Liquid Chemical Delivery Systems JW-300-LDS

-

DPR1 Ultra High Purity Two Stage Dual Stage Pressure Reducing Regulator Semiconductor Grade Regulators

-

High Purity High Pressure Gas Cylinder Pressure Regulators Pressure Reducing Valve JSR-1E Series

-

Single Stage Wall And Cabinet Mounting Pressure Control Panels JSP-2E Series For High Purity Gases

-

High Pressure High Flow Specialty Gas Control Panel With Diaphragm Valve , 3000Psig Oxygen Control Medical Changeover Manifold Panel

-

JR1000 Series UHP Ultra High Purity Single Stage Pressure Reducing Regulator And Low To Intermediate Flow