Blog

Jewellok is a professional pressure regulator and valve manufacturer and supplier.

How Does A Helium Gas Changeover Manifold Work?

- Pressure Regulator Valve Manufacturer

- Acetylene Gas Changeover Manifold, Acetylene Gas Pressure Regulator, argon gas changeover manifold, argon gas pressure regulator, Auto Gas Changeover Manifold System, Automatic gas changeover manifold, Automatic LED-type Oxygen Manifold System, best gas changeover manifold, Best gas changeover manifold for laboratories, BURSAN Gas Changeover Manifold, Carbon Dioxide Gas Changeover Manifold, Carbon Dioxide Gas Pressure Regulator, Changeover Manifold For Oxygen Nitrogen Co2, China Oxygen Pressure Regulator, gas changeover manifold, Gas manifold for aquaculture oxygen supply, Gas Manifold for Oxygen Supply, helium gas changeover manifold, helium gas changeover manifold manufacturer, helium gas changeover manifold supplier, helium gas changeover manifold supplier philippines, helium gas changeover manifold work, helium gas pressure regulator, High Flow Oxygen Regulator, High Pressure Gauge for Oxygen Regulator 0-4000 psi, High Pressure Oxygen Regulator, High Volume High Pressure Oxygen Regulators, High Volume Oxygen Regulators, LCD Automatic Oxygen Manifold, Low and High Pressure Gauges for Oxygen Regulator, low pressure oxygen regulator, Medical oxygen high pressure regulator, nitrogen gas changeover manifold, oxygen gas changeover manifold, Oxygen Gas Pressure Regulator, Propane Gas Changeover Manifold

- No Comments

How Does A Helium Gas Changeover Manifold Work?

In the intricate ecosystems of modern hospitals, cutting-edge scientific research, and high-stakes manufacturing, the continuous supply of specific gases is not merely a convenience—it is the very lifeblood of critical processes. When that gas is helium, the stakes are particularly high. As a noble gas with unique properties, helium is both indispensable and, crucially, a non-renewable resource subject to supply volatility. An unexpected interruption in helium flow can halt an MRI scan in a hospital, ruin years of scientific research, or compromise the integrity of a semiconductor wafer worth millions. The helium gas changeover manifold is the sophisticated piece of engineering that stands as a bulwark against such catastrophic disruptions. It ensures a seamless, uninterrupted transition from a primary gas supply to a secondary reserve, all without a flicker in pressure. But how does this system achieve such a critical feat?

At its heart, a helium gas changeover manifold is an automated sentinel, a device that continuously monitors gas pressure and executes a pre-programmed switch at the precise moment the primary source is depleted. Its operation is a masterclass in practical pneumatics, leveraging the fundamental principles of pressure differentials, spring mechanics, and one-way check valves to create a foolproof system. Understanding its function is key to appreciating its role in safeguarding some of the most advanced technologies in the world.

The Critical Role of Helium: Why the Manifold is Essential

Before dissecting the components, it’s vital to understand why helium demands such a reliable delivery system. Unlike argon, which is abundant in the atmosphere, helium is captured from natural gas reserves and is finite. Its applications are also uniquely sensitive:

- Medical Imaging: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scanners use liquid helium to cool their superconducting magnets to near-absolute zero. While the magnet is typically sealed, the boil-off gas and systems that rely on gaseous helium for cooling and purge functions cannot be interrupted without risk of a “quench”—a catastrophic event where the magnet loses superconductivity, resulting in millions of dollars in damage and downtime.

- Analytical Chemistry: Gas Chromatography (GC) and Mass Spectrometry rely on helium as a carrier gas. Any fluctuation or loss of pressure during a run introduces noise, ruins calibration, and invalidates results, potentially wasting priceless samples and weeks of preparation.

- Aerospace & Leak Testing: Helium’s small atomic size makes it the ideal tracer gas for detecting microscopic leaks in fuel systems, spacecraft, and high-vacuum chambers. A break in the helium supply during a test renders the entire procedure useless and compromises safety.

- Semiconductor Manufacturing: In the fabrication of microchips, helium is used for its excellent thermal conductivity in plasma etching and chemical vapor deposition chambers. A loss of cooling can destroy entire batches of wafers.

The changeover manifold is the device that prevents these expensive and dangerous failures, providing the continuous flow that these processes demand.

Deconstructing the System: Core Components of the Manifold

A standard two-cylinder helium gas changeover manifold is an assembly of several key components, each playing a specific role in the orchestrated dance of gas switching:

- Inlet Valves (Primary and Reserve): These are manual shut-off valves, one for each gas cylinder. They allow technicians to safely isolate a cylinder for replacement without depressurizing the entire system.

- First-Stage Pressure Regulators: Arguably the most critical components for stable operation, these regulators are attached to each cylinder inlet. They take the extremely high and variable pressure from the helium cylinder (which can be up to 2,200 psi / 150 bar when full) and reduce it to a consistent, lower “intermediate” or “line” pressure. This is typically set between 100-150 psi (7-10 bar). This step is crucial as it provides a stable pressure signal for the changeover mechanism to monitor.

- The Changeover Valve (The Automated Brain): This is the centerpiece of the system. It is a specialized valve with two inlets (from the primary and reserve regulators) and a single outlet. Inside, a sensitive diaphragm or piston is constantly exposed to the pressure from the primary supply line. A calibrated spring opposes this pressure. The valve is pre-set to actuate at a specific “changeover pressure.”

- Non-Return Valves (Check Valves): These one-way valves are integrated within or installed immediately downstream of the changeover valve. They act as critical gates, preventing helium from the active (reserve) supply from flowing back into the inactive (primary) line. This ensures no cross-contamination and maintains the direction of flow.

- Pressure Gauges: The manifold features two types of gauges:

- Cylinder Content Gauges: Positioned after each inlet valve, these show the high pressure inside each individual cylinder, providing a rough estimate of how much gas remains.

- Delivery Pressure Gauge: This shows the stable, regulated intermediate pressure being supplied to the downstream application.

- Outlet Valve: A manual valve that controls the final gas flow from the manifold to the point of use (e.g., the MRI machine or GC instrument).

- Alert Mechanism: This is the system’s communication tool. It is typically a brightly colored visual flag (often red) that pops up when the system switches to reserve. On more advanced models, this mechanical action can also trigger a pneumatic or electrical micro-switch to activate an audible alarm, a warning light, or even send a signal to a building management system.

The Operational Sequence: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

The elegance of the changeover manifold is revealed in its step-by-step operation, a sequence that ensures zero interruption in gas flow.

Phase 1: Normal Operation – Primary Supply Active

Initially, both the primary and reserve cylinders are full, and their respective inlet valves are open. High-pressure helium from the primary cylinder flows through its first-stage regulator, which steps the pressure down to a steady 100 psi. This regulated gas now enters the “primary” inlet of the changeover valve.

Inside the changeover valve, the 100 psi pressure exerts a force on the diaphragm, compressing the internal calibration spring. This force holds the valve’s internal mechanism in the “primary” position. In this state, the flow path from the primary inlet is wide open, while the pathway from the reserve inlet is mechanically blocked. The check valve on the primary side is held open by the flow, while the reserve-side check valve remains sealed. Helium flows unimpeded from the primary cylinder, through the changeover valve, and out to the application. The system is in a state of equilibrium, and the alert flag remains down.

Phase 2: Depletion and the Automatic Switchover

As the primary cylinder is consumed, the pressure inside it drops. The first-stage regulator is designed to maintain a constant 100 psi output until the cylinder pressure falls very close to this delivery pressure. Once this point is reached, the regulator can no longer compensate.

The pressure in the line between the primary regulator and the changeover valve begins to decay. When this pressure falls below the manifold’s pre-set changeover threshold (for example, 50 psi), the force on the diaphragm is no longer sufficient to overcome the strong calibration spring.

The spring now acts, swiftly moving the internal mechanism of the changeover valve. This action is instantaneous and has two simultaneous effects:

- It mechanically shuts off the flow path from the depleted primary inlet.

- It opens the flow path from the full reserve inlet.

The regulated 100 psi helium from the reserve cylinder immediately fills the changeover valve. The moment the primary side pressure dropped, its associated check valve snapped shut, preventing any of the new reserve gas from back-flowing into the empty primary line. The gas flow is now seamlessly sourced from the reserve cylinder. The entire transition occurs in milliseconds—far faster than any sensitive instrument or process can detect.

Phase 3: Alarm and Resetting the System

The physical movement of the changeover valve’s internal mechanism is linked to the alert system. As the valve shifts from “Primary” to “Reserve,” it triggers the bright red flag to become visible and may activate an electronic alarm.

This is the manifold’s unambiguous signal: “The primary cylinder is empty. I have switched to reserve to maintain your process, but the empty cylinder must be replaced immediately.” A technician can then respond proactively. They would close the inlet valve on the empty primary cylinder, safely vent the residual pressure from that side of the manifold, replace the cylinder, and open the valve on the new primary cylinder. Once the primary side is repressurized, the technician manually resets the changeover valve (usually via a button or lever). This action shifts the valve back to the primary position, closes the reserve inlet, lowers the alert flag, and re-arms the system for the next cycle.

Special Considerations for Helium

While the principle is the same as for argon, helium’s small atomic size and its status as a critical resource demand extra attention. Manifolds designed for helium must be built to the highest standards of leak integrity. Every connection, valve stem, and seal is precision-engineered to prevent the minute leaks that would be trivial with larger gas molecules but are costly and problematic with helium. Furthermore, in many facilities, these manifolds are part of a larger, bulk gas management system that may include liquid helium dewars and elaborate distribution networks, all monitored for usage and efficiency.

Conclusion

The helium gas changeover manifold is a paradigm of robust and intelligent design. It transforms a vulnerable single-point failure—the finite gas cylinder—into a managed, redundant system. By harnessing simple physical principles, it performs a function that is vital for the continuity of healthcare, scientific discovery, and technological innovation. It operates silently and reliably in the background, a mechanical sentinel ensuring that the flow of this precious and irreplaceable gas never falters. In a world increasingly dependent on precision and reliability, the helium changeover manifold is not just a piece of plumbing; it is a fundamental pillar of modern industrial and scientific infrastructure.

For more about how does a helium gas changeover manifold work, you can pay a visit to Jewellok at https://www.jewellok.com/ for more info.

Recent Posts

What is a Xenon (Xe) Ultra High Purity Gas Regulator?

Five Key Considerations When Choosing a TMA Gas Changeover Manifold

Tags

Recommended Products

-

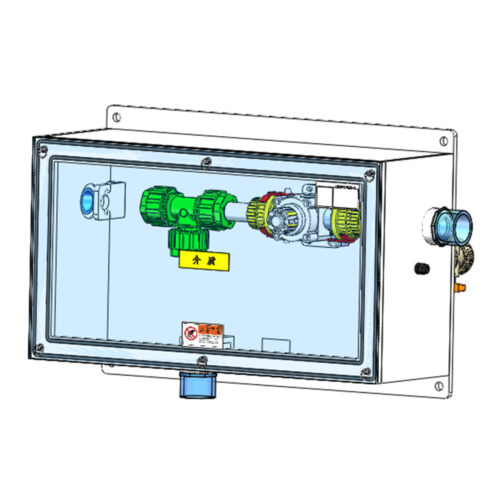

Semi Automatic Gas Cabinet Gas Panels High Purity Gas Delivery Systems JW-200-GC

-

764L Stainless Steel Union Tee High Purity Fitting Union Tee Reducing Tubing Connection

-

High Purity High Pressure 316 Stainless Steel Ball Valves JBV1 Series From High Pressure Ball Valve Manufacturer And Supplier In China

-

Scrubber Tail Gas Treatment Cabinet Waste Gas Treatment Wet Scrubber Exhaust Gas Treatment Spray Tower

-

High Purity High Pressure Specialty Gas Pressure Regulators Specialty Gases Pipeline Engineering Equipments Manufacturer And Supplier

-

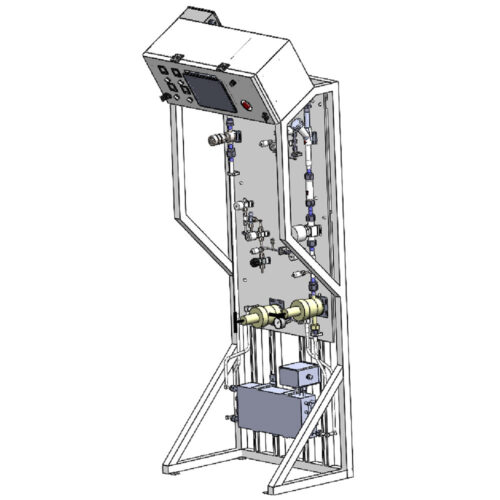

Fully Automated Gas Cabinet Gas Rack Gas Delivery Systems JW-300-GR

-

Ultra High Purity Stainless Steel Compressed Gas Changeover Manifold Panel System For Integrated Gas Supply System

-

Ultra High Purity Trimethylaluminum TMA Gas Cabinet Liquid Delivering Cabinet Used For Specialty Gas Delivery System In Semiconductor